You will begin a long journey that extends from the emergence of the first civilizations in the Nile Valley (Egypt), the most fertile place in North Africa, and in Mesopotamia (Tigris and Euphrates), where a product of these civilizations was mathematics.

Among other things, the ancient Egyptians developed a numerical system for the purpose of counting, based on different symbols for ones, tens, hundreds, and thousands. Inscriptions of sequential numbers are found on the wall of Thutmose III in the Temple of Karnak. Later, the Babylonians surpassed the Egyptians in arithmetic and created the first modern numbering system.

In 500 BC, the oldest school of mathematics was founded by Pythagoras in southern Italy. It was particularly concerned with the study of the properties of numbers and the measurement of objects and gave importance to the triangular numbers 1, 3, 6, 10, 15 and the perfect square numbers 1, 4, 9, 16, 25. The study of pictorial numbers was passed on to us from Hippolytus’s Arithmetic to the age of globalization.

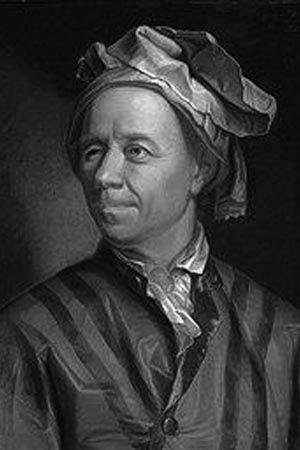

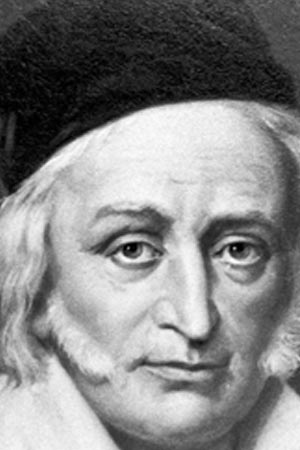

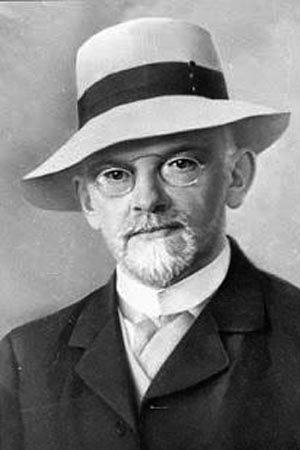

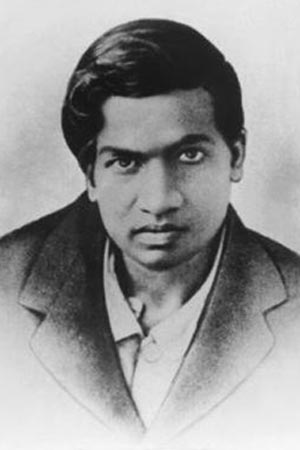

Later, the solution of Fermat’s Grand Theorem was introduced as a fine example of global collaboration in our time, and as one of the most important mathematical achievements of the 20th century.Portraits of mathematicians are scattered throughout the museum, and you will meet the people who are credited with this wonderful science such as Greeks, Arabs, Germans, Indians and others from all over the world who were united by their marvelous mathematical intellect, and their theories are the living witness to their immortality.